Work In Prototypes

WIP / KeepyUps

If you've spent some time on this site, you've probably seen there's quite a variety of work here. I find it really rewarding to bring ideas to life however I can, which often ends with prototypes that get forgotten and unfinished. So, to keep some of those ideas alive, I've launched a YouTube channel, Work In Prototypes, to document my process and builds.

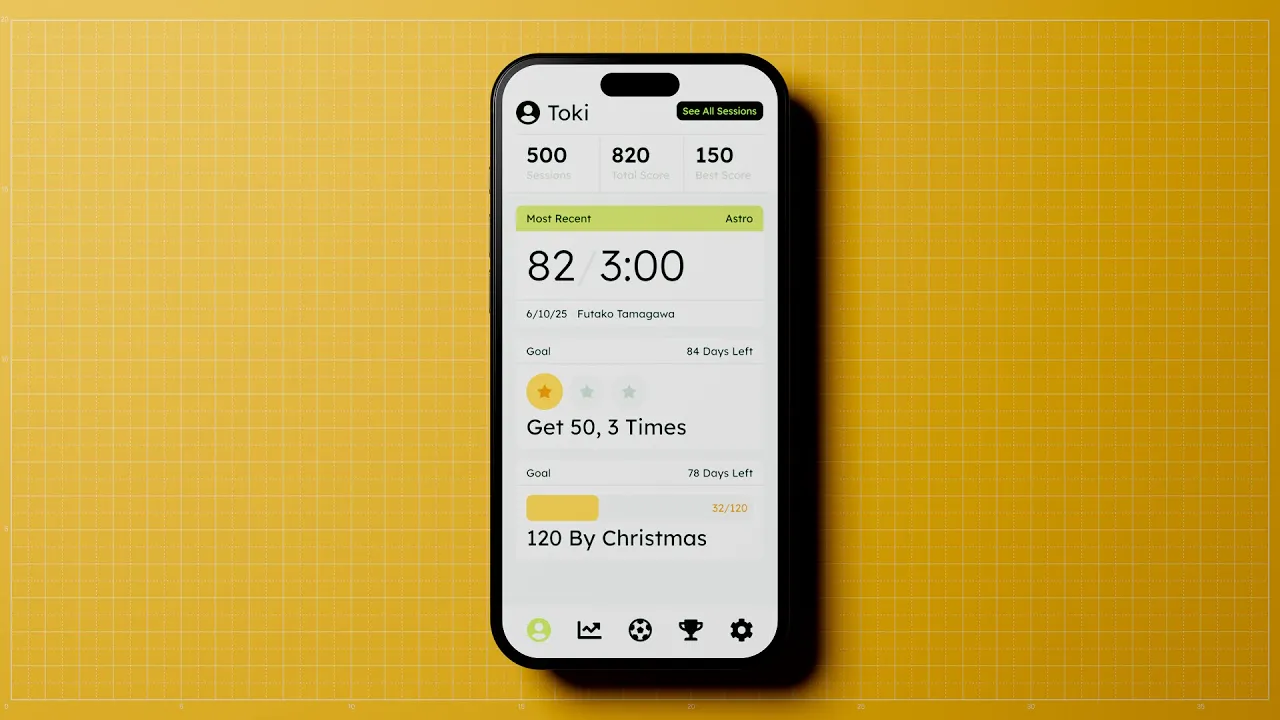

This is the first project: KeepyUps, a football keep-ups tracking prototype for me and my son. Here's how building it went:

Keeping Track of Goals

My eldest loves playing football.

He is part of a local team that does well in tournaments, and as part of their training his coach set a challenge to help them improve: "Every player should be able to do keep-ups for at least a minute." This started a long journey of going to parks and quiet streets as often as we could to give him the chance to practise. I would stand there counting, watching his feet, trying not to lose track of each attempt as the numbers rose and fell.

Over time the numbers began to improve, but we also started losing track of how well he was really doing. My wife suggested a paper chart that my son could fill in after every session with his highest count. This turned out to be a great unlock for his confidence and his improving footwork. He could now see his best scores, and each new training session became a personal match to beat himself.

We even took the chart with us on a recent family trip to the UK, so he could keep it stuck on his grandparents' fridge as a reminder to keep practising. The fridge is where the chart stayed, forgotten by a silly Daddy, but the motivation to keep improving stayed with him. That sparked the idea of creating a digital version I could keep in my pocket, use anywhere in the moment, and still show him his journey.

The Laws of the Game

To get a prototype off the ground quickly, I set a few clear constraints:

It had to be free:

Apart from the tools needed to build it, there was no budget.

It had to be mobile:

This needed to be used outdoors, well away from fragile windows.

I wanted to try something new:

This would be my first proper attempt at building a full app with vibe coding learnt from past experiments.

It had to work without looking at the screen:

When I count keep-ups, my eyes are on him, not my phone. Until now, I had been using my fingers to keep track, so the app needed to be just as intuitive.

So, with some ground rules in place I started by mapping a simple flow for the screens I would need to build something usable. Thanks to a phone being able to record far more contextual information than my fingers, I listed the kinds of data I wanted to capture in each session. Multiple attempts, surface type, location, weather, time, and so on all became available to work with. The original paper chart had been great at visualising progress and boosting motivation, so making meaningful use of this data was important.

In previous experiments I had been enamoured with a Cursor-to-Swift workflow, but in this case it was not going to work with my constraints, particularly the cost and friction of keeping an iOS app running without repeated installs. So, in the spirit of trying something new, I chose to build a web app using Firebase for data and Netlify for hosting.

A short list of features turned into rough sketches. They were just enough to help me think about how to brief Cursor and explore what kind of build might work, however, the first few rounds of generated screens were rough.

I am still learning how to prompt effectively, and I often found myself going in circles with Cursor. We would push one approach for too long when a simpler solution probably existed. After some back and forth, and after deliberately ignoring some of the visual decisions Cursor was making, I arrived at a working prototype I could take outside and test.

Unsurprisingly, but unfortunately, it did not really work. Data was not always recorded. Rapid taps to log kicks triggered zoom gestures. The problems became obvious as soon as it left my desk. Still, I felt that it could improve. I adjusted how I prompted, narrowed the scope, isolated specific problems, and became explicit about what I did not want changed.

That helped, but I also needed to step back and feel comfortable with the project again. I shifted my focus to the UI and the details. I spent time mood boarding, exploring colour, and thinking carefully about how to record keep-ups without constantly checking the screen. This was not just about usability. If it did not feel good to use, I knew I would not keep coming back to it.

In the spirit of trying something new, I also knew that leaving the visuals entirely to Cursor would not be enough. I created a small visual library based on previous work in Figma, with the intention of carrying that language into the final app. I am not convinced I approached this in the right way. There are now experiments with Figma's MCP being hooked up to Cursor for closer one-to-one translations. But after undoing a significant amount of unsolicited visual work, I ended up somewhere close to what I had in mind.

After many more iterations, merging visual decisions with functional improvements, I arrived at something that is still far from finished.

But it works.

More importantly, it is something I can take with me. Something I can use to track my son’s progress. Something I can show him, so he can see how far he has come and feel motivated to keep going.

For now, this is good enough, and he’s up to 1m 30s now!